Polar ice loss quickens, raising seas

Richard Black

Environment correspondent, BBC News

The Greenland ice sheet is losing its mass faster than its southern counterpart

Ice loss from Antarctica and Greenland has accelerated over the last 20 years, research shows, and will soon become the biggest driver of sea level rise.

From satellite data and climate models, scientists calculate that the two polar ice sheets are losing enough ice to raise sea levels by 1.3mm each year.

Overall, sea levels are rising by about 3mm (0.12 inches) per year.

Writing in Geophysical Research Letters, the team says ice loss here is speeding up faster than models predict.

They add their voices to several other studies that have concluded sea levels will rise faster than projected by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its landmark 2007 assessment.

By 2006, the Greenland and Antarctic sheets were losing a combined mass of 475Gt (gigatonnes - billion tonnes) of ice per year.

On average, loss from the Greenland sheet is increasing by nearly 22Gt per year, while the much larger and colder Antarctic sheet is shedding an additional 14.5Gt each year.

If these increases persist, water from the two polar ice sheets could have added 15cm (5.9 inches) to the average global sea level by 2050.

A rise of similar size is projected to come from a combination of melt water from mountain glaciers and thermal expansion of seawater.

"That ice sheets will dominate future sea level rise is not surprising - they hold a lot more ice mass than mountain glaciers," said lead author Eric Rignot from Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California.

"What is surprising is this increased contribution by the ice sheets is already happening."

Grace on fire

Extending this rate of ice loss forward to 2100, the sea level rise contribution from the two ice sheets alone is calculated at 56cm (22 inches).

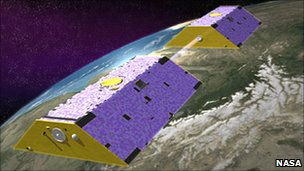

The twin Grace satellites orbit the Earth in close formation, detecting tiny variations in gravity

By contrast, the IPCC in 2007 projected a maximum rise of 59cm, while acknowledging this was likely to be an under-estimate because understanding of processes happening on ice sheets was insufficient to enable reliable estimates to be made.

Since 2007, several other research groups using different methods have concluded that a figure between one and two metres is likely - which would have profound consequences for island nations and countries with long, low coastlines such as Bangladesh.

"If present trends continue, sea level is likely to be significantly higher than levels projected by the IPCC," said Dr Rignot.

"Our study helps reduce uncertainties in near-term projections of sea level rise."

The new research combined two different methodologies.

One calculates ice gain and loss through combining various types of satellite reading and data taken on the ground, for example the thickness of the ice sheet and the speed at which glaciers are moving.

The second dataset comes from Nasa's Grace mission, which uses twin satellites to measure variations in the Earth's gravitational pull.

Ice loss causes a fractional reduction in gravity at that point on the Earth's surface.

Two years ago, this mission surprised some in the research community by showing that even the vast and frigid East Antarctic ice sheet was losing some of its mass to the oceans.