The pristine Arctic has become a garbage trap for 300 billion pieces of plastic

Chris Mooney

Washington Post

Drifts of floating plastic that humans have dumped into the world's oceans are flowing into the pristine waters of the Arctic as a result of a powerful system of currents that deposits waste in the icy seas east of Greenland and north of Scandinavia.

In 2013, as part of a seven-month circumnavigation of the Arctic Ocean, scientists aboard the research vessel Tara documented a profusion of tiny pieces of plastic in the Greenland and Barents seas, where the final limb of the Gulf Stream system delivers Atlantic waters northward. The researchers dub this region the 'dead end for floating plastics' after their long surf of the world's oceans.

The researchers say this is just the beginning of the plastic migration to Arctic waters.

'It's only been about 60 years since we started using plastic industrially, and the usage and the production has been increasing ever since,' said Carlos Duarte, one of the study's co-authors and director of the Red Sea Research Center at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia. 'So, most of the plastic that we have disposed in the ocean is still now in transit to the Arctic.'

The results were published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances. The study was led by Andrés Cózar of the University of Cádiz in Spain along with 11 other researchers from universities in eight nations: Denmark, France, Japan, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The researchers estimated that about 300 billion pieces of tiny plastic are suspended in these Arctic waters right now, although they said the amount could be higher. And they think there is even more plastic on the seafloor.

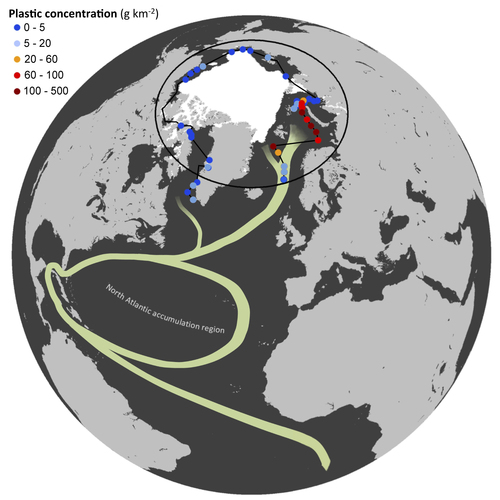

Here's a map the researchers provided, showing the ocean circulation in the Atlantic and where that, in turn, has delivered plastic particles:

Several factors support the idea that the plastic entered these waters via ocean currents rather than local pollution. First, the Arctic has a very small population that is unlikely to directly contribute so much waste. Also, the aged and weathered state of the plastic, and the tiny size of the pieces found, suggested that it had traveled the seas for decades, breaking down along the way.

'The plastic pieces that may have been initially inches or feet in size, they have been brittled by exposure to the sun and then fragmented into increasingly smaller particles, and eventually led to this millimeter-size plastic that we call microplastic,' Duarte said. 'That process takes years to decades. So the type of material that we're seeing there has indications that it has entered the ocean decades ago.'

Finally, the study didn't find much plastic in the rest of the Arctic ocean beyond the Greenland and Barents seas, also suggesting that currents were to blame. Instead the plastic had accumulated where the northward-flowing Atlantic waters plunge into the Arctic depths. Presumably, the plastic then lingers at the surface.

The Greenland and Barents seas contained 95 percent of the Arctic's plastic, the research found (the ship sampled 42 sites across the Arctic Ocean). The Barents Sea happens to be a major fishery for cod, haddock, herring and other species. A key question will be how the plastic is affecting these animals.

Here's a collage that the researchers provided showing the types of plastic they found:

The study's results sent a troubling message to one researcher who has also focused on the consequences of plastic debris in the oceans and other waterways.

'Isn't it kind of ironic that days before Earth Day there is more demonstrated proof of widespread contamination of our plastic waste in places that are so far from the human footprint and thus locations we consider to be pristine,' said Chelsea Rochman, a marine ecologist at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study but praised it as 'a great contribution to the field.'

The ocean circulation system in the Atlantic responsible for this plastic transport is part of a far larger 'thermohaline' ocean system driven by the temperature and salt content of oceans. It is also often called an 'overturning' circulation because cold, salty waters sink in the North Atlantic and travel back southward at deep ocean depths.

As humans now put 8 million tons of plastic in the ocean annually, learning how such currents affect the plastic's global distribution is a key scientific focus. Researchers, including Duarte, previously found that plastic slowly travels the world's oceans but tends to linger in five 'gyres,' or circular ocean currents in the subtropical oceans in both the northern and southern hemispheres. One of those gyres is located in the Atlantic, which then feeds the Arctic.

Scientists noted that the vast majority of ocean plastic becomes lost before it reaches the Arctic. They aren't sure where most of the plastic falls out and are researching to determine those locations. 'The plastic that escapes those traps is the one that actually makes it into the Arctic,' Duarte said. 'But when it enters the Arctic, there is no way out, it just stays there and is stuck there.'

Because it takes such a long time for plastic to travel across the world in ocean currents, the study concludes that the current waste is largely the work of North Americans and Europeans, who dumped it in the Atlantic. Waste from other parts of the world that dump huge volumes of plastic into the oceans is still in transit.

Rochman said she feared that as the Arctic becomes more accessible because of ice melt linked to climate change, more plastic could wash in. 'As the ice melts, we may see increasing concentrations of plastic in the Arctic due to the opening of passageways for vessels and plastics in surface currents,' she said, 'as well as plastics in the ice becoming free to float and interact with marine animals upon melting.'